History

Social and economic history

Piddington's early history is outlined here. For much of its existence since then, the village has relied mainly on farming and rural occupations, with the surrounding land largely held by a small number of landowners.

The villagers supplemented their wages by using common land to graze their own animals and making use of Piddington's ancient right of access to Bernwood Forest. These woodlands were of great importance to the rural economy, providing not only timber for building, fuel and making small household items, but also food, including wildlife, fruit, nuts and herbs. Enclosure of the land to increase its profitability had been practised on a small scale before, but the Enclosure Acts passed in the second half of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th caused a huge upheaval in rural life.

During the 18th century, enclosures were regulated by Parliament; a separate Act of Enclosure was required for each village that wished to enclose its land. In 1801, Parliament passed a General Enclosure Act, which enabled any village, where three-quarters of the landowners agreed, to enclose its land.

Large areas of land were bought up by wealthy men, like Sir Edward Turner, second Baronet of Ambrosden, who were able to charge higher rents on land for which they had been granted an enclosure award. Awards were based on land held at the time of the Act and tenants were carefully selected, their tenancy agreements committing them to systematic husbandry in order to maintain and improve the land. The remaining common fields and much of the common or ‘waste’ lands, on which all householders had some grazing rights, passed into the ownership of a few.

Although enclosure of the land did improve the quality and profitably of the land and encourage experimentation with crops and animal husbandry, it had many negative outcomes for the less wealthy inhabitants. Farmers (known as customary tenants) who failed to prove legal entitlement to land their families had worked for generations were evicted, as were villagers who owned no land and had kept animals on common pasture (common land was allocated to other farmers through enclosure). Poor farmers, allocated small plots of land, were unable to compete with large landowners. Many lost their land when their businesses failed Many poor, evicted peasants moved to industrial cities to find work. Having lost their means of self-sufficiency they were forced to accept low wages and poor conditions.

In 1758 Piddington was subject to an Enclosure Act. 'The distribution of the awards was uneven, with Sir Edward Turner being granted 499 acres of freehold and a further 36 acres of leasehold land (circa 40% of the lands enclosed) while at the other end of the scale 15 smallholders got plots mostly under 5 acres and a further seven a mere half acre each, common for a horse. This seems to have given rise to ... bitterness and animosity ... In 1791 the Piddington Parish Records report that 25 owners and occupiers agreed to prosecute at their own expense all persons guilty of damaging the property. They claimed that: persons had broken down, destroyed, and carried away our hedges, gates and other fences, and have robbed our gardens, orchards, hen roosts, faggot piles, and other outbuildings. The fact that this report is more than 30 years after the passing of the Act suggests that many of those who had lost their livelihood had stayed on in the district as agricultural labourers, seasonal workers, gypsies and even beggars' (Green, 2000, p.119).

The villagers supplemented their wages by using common land to graze their own animals and making use of Piddington's ancient right of access to Bernwood Forest. These woodlands were of great importance to the rural economy, providing not only timber for building, fuel and making small household items, but also food, including wildlife, fruit, nuts and herbs. Enclosure of the land to increase its profitability had been practised on a small scale before, but the Enclosure Acts passed in the second half of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th caused a huge upheaval in rural life.

During the 18th century, enclosures were regulated by Parliament; a separate Act of Enclosure was required for each village that wished to enclose its land. In 1801, Parliament passed a General Enclosure Act, which enabled any village, where three-quarters of the landowners agreed, to enclose its land.

Large areas of land were bought up by wealthy men, like Sir Edward Turner, second Baronet of Ambrosden, who were able to charge higher rents on land for which they had been granted an enclosure award. Awards were based on land held at the time of the Act and tenants were carefully selected, their tenancy agreements committing them to systematic husbandry in order to maintain and improve the land. The remaining common fields and much of the common or ‘waste’ lands, on which all householders had some grazing rights, passed into the ownership of a few.

Although enclosure of the land did improve the quality and profitably of the land and encourage experimentation with crops and animal husbandry, it had many negative outcomes for the less wealthy inhabitants. Farmers (known as customary tenants) who failed to prove legal entitlement to land their families had worked for generations were evicted, as were villagers who owned no land and had kept animals on common pasture (common land was allocated to other farmers through enclosure). Poor farmers, allocated small plots of land, were unable to compete with large landowners. Many lost their land when their businesses failed Many poor, evicted peasants moved to industrial cities to find work. Having lost their means of self-sufficiency they were forced to accept low wages and poor conditions.

In 1758 Piddington was subject to an Enclosure Act. 'The distribution of the awards was uneven, with Sir Edward Turner being granted 499 acres of freehold and a further 36 acres of leasehold land (circa 40% of the lands enclosed) while at the other end of the scale 15 smallholders got plots mostly under 5 acres and a further seven a mere half acre each, common for a horse. This seems to have given rise to ... bitterness and animosity ... In 1791 the Piddington Parish Records report that 25 owners and occupiers agreed to prosecute at their own expense all persons guilty of damaging the property. They claimed that: persons had broken down, destroyed, and carried away our hedges, gates and other fences, and have robbed our gardens, orchards, hen roosts, faggot piles, and other outbuildings. The fact that this report is more than 30 years after the passing of the Act suggests that many of those who had lost their livelihood had stayed on in the district as agricultural labourers, seasonal workers, gypsies and even beggars' (Green, 2000, p.119).

|

The burden of providing for the increasing numbers of the needy fell upon the local parishes, giving rise to high poor rates (funds collected through church rates to provide for the poor of the parish).

In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act reduced access to outdoor relief and made help available largely through the workhouses. They alleviated the parish's financial burden and were also intended as a deterrent. Ambrosden parish became part of the Bicester Poor Law Union, which built a workhouse in Market End, Bicester. The problems of poverty and underemployment in the agricultural sector continued throughout the 19th century and were key factors in many families leaving this area between 1850 and 1880, some emigrating to America, Australia and Canada via assisted passage schemes. |

Before 1870 there was no national system of education, and rural communities relied on the voluntary efforts of individuals, often clergymen and philanthropists concerned at the growing numbers of illiterate poor. In Piddington a Sunday school was founded in 1818. At the beginning of the century the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Church of England began to set up 'National schools' using a method whereby children were grouped by ability, with the most able being taught by a teacher and then passing the knowledge down the chain (later called the pupil-teacher system, in use until the 1930s). Piddington's Sunday school became a day school in 1858, supported by the National Society, and a new school building was erected in 1859. This date for the opening of Piddington School differs from that of 1863, which appears in A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred, and has been quoted widely since publication in 1957. Piddington resident David Cook long doubted this date and finally (in July 2020) unearthed printed confirmation of the earlier date. He explains:

The History of Oxfordshire 'Bullingdon Hundred' narrative of Piddington School states 'A new building was said in 1887 to have been erected in 1863 with accommodation for 100 children.' This date has however been quoted widely since publication in 1957. I have known for many years that the 1863 date was not correct. The schoolmaster’s wife Barbara Green gave birth to young Albert in the summer of 1860. Finding newspaper reports relating to the building and opening of the school in 1858 and 1859 has provided further confirmation. At one time I thought that the 1863 date could relate to an 'official opening' of the school, sometime after its operation commenced. I have found nothing relating to the school opening at that time but unearthed the newspaper articles shown above. I have found one event that took place in the school room in January 1863. It is described as the second annual gathering.' This was a very interesting event, more of which another day.

The transcript of parish records shows the opening date of the school: 5th September 1859. This is supported by further transcripts of the school accounts showing income, donations, and expenditure from 1859 for each year to 1869.

(Cook, 2020, Chapter 13)

Below are links to the printed sources concerning the opening of Piddington School that David Cook has brought to light. I am extremely grateful to for allowing me to reproduce them here.

Laying the Foundation Stone, Bicester Advertiser, 13 November 1858

Laying the Foundation Stone, Oxford Journal, 20 November 1858

Fund for the Schoolmaster’s House, transcript of Parish Records, 1858.

David has been able to identify several of the subscribers to this fund, and has also discovered some interesting information about Piddington's first schoolmaster (Cook, 2020, Chapters 13 and 14).

Bishop of Oxford’s sermon at Piddington, Oxfordshire Telegraph, 18 May 1859

Tea party to celebrate the opening of Piddington School, Oxfordshire Telegraph, 1 June 1859

Tea party to celebrate the opening of Piddington School, Bicester Advertiser, 4 June 1859

Laying the Foundation Stone, Bicester Advertiser, 13 November 1858

Laying the Foundation Stone, Oxford Journal, 20 November 1858

Fund for the Schoolmaster’s House, transcript of Parish Records, 1858.

David has been able to identify several of the subscribers to this fund, and has also discovered some interesting information about Piddington's first schoolmaster (Cook, 2020, Chapters 13 and 14).

Bishop of Oxford’s sermon at Piddington, Oxfordshire Telegraph, 18 May 1859

Tea party to celebrate the opening of Piddington School, Oxfordshire Telegraph, 1 June 1859

Tea party to celebrate the opening of Piddington School, Bicester Advertiser, 4 June 1859

In 1925 Piddington School was reorganised as a junior and infants' school, with the senior pupils attending Bicester County School. It closed in 1967 and Five Acres at Ambrosden then became the school for the children of Piddington (25 children from the village attended it in 1968); it is still the catchment school for Piddington. The school room was used as a meeting room for the village for smaller events until it was sold in 1977/8, and converted to private houses.

|

In 1850 the LNWR link between Oxford and Bletchley was constructed, passing through Bicester. The railway gave a boost to this region by offering opportunities for farmers to send their produce to London and providing work for several of the landless poor.

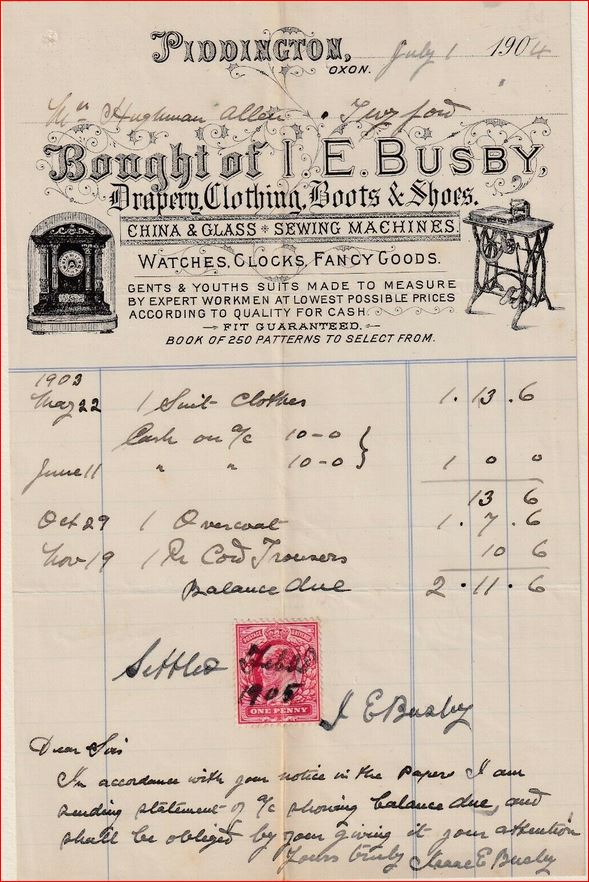

Gradually, manufactured goods spread throughout the villages, excursions to Oxford and beyond became possible and the development of post and telegraph offices and easy availability of London newspapers brought increasing changes to daily life. Surprisingly, Piddington had quite a range of shops. The 1861 census shows a butcher, a baker, three grocers, two public houses, a tailor and two shoemakers. In about 1910 the Great Western Railway built a new main line linking Ashendon Junction to Aynho Junction to complete a new high-speed route between its termini at London Paddington and Birmingham Snow Hill. The line passes within a few hundred metres of Piddington. British Railways closed the station at Blackthorn in 1953 and the station called Brill and Ludgershall in 1963 but the railway remains open as part of the Chiltern Main Line. In 1941 the Bicester Military Railway was built. It connects with the Varsity Line just west of Bicester, runs through the villages of Ambrosden and Arncott and terminates at Piddington, serving various military depots en route. It remains in use today. The entry for Piddington in Kelly's Directory of 1935 gives some detail of life here at that time. |

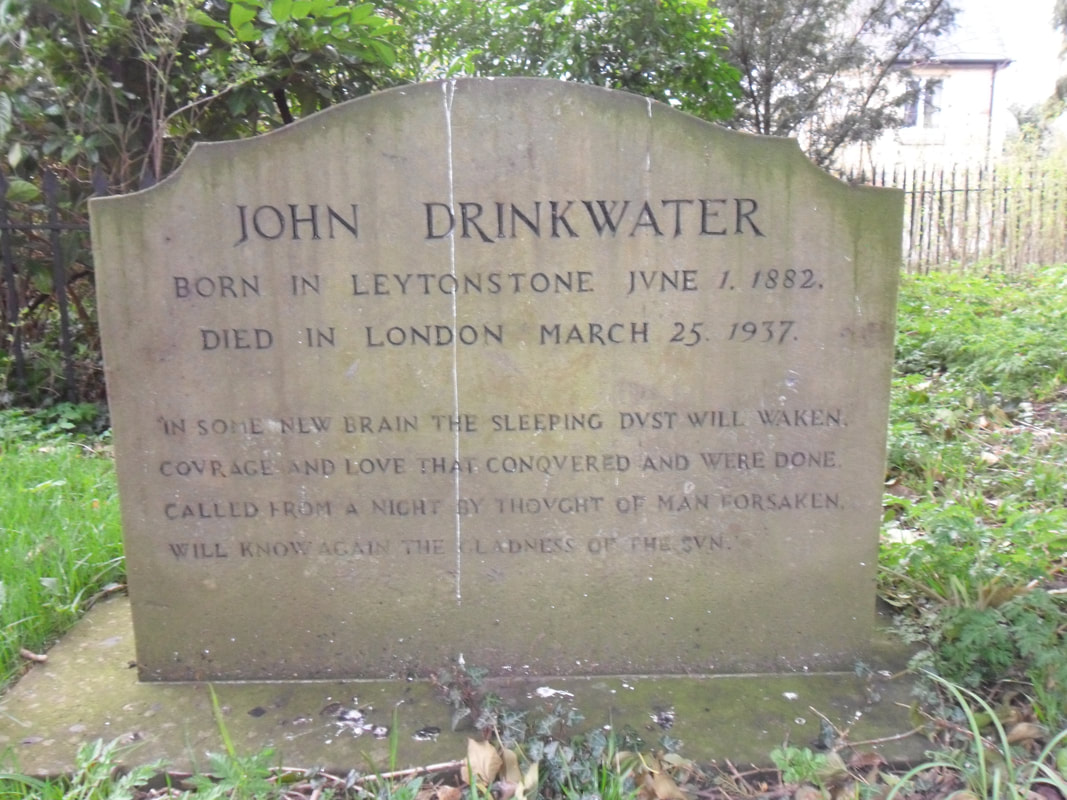

John Drinkwater (1882–1937) who became one of the Dymock poets and a playwright working with the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, is buried in St Nicholas' churchyard.

Flora Thompson, author of Lark Rise to Candleford, had connections with Piddington, as her grandmother, Martha Wallington, lived in Brown's Piece. Notes on the history of this house were supplied by Margaret Tapper, who lived in this house until her death in 2018. You can hear more about the Tapper family here. Select Clip 4 from People and Places: Piddington. Her husband, Thomas, was a famous racing driver and started up Haddenham Airfield, which played an important role in the Second World War. Read more about him here.

In Lark Rise to Candleford, Flora Thompson describes a garland made by the schoolchildren of Juniper Hill (Lark Rise in the books) in the 1880s. It consisted of a bell-shaped frame covered in greenery and flowers. Below are a couple of photographs of just such garlands in Piddington in the mid 20th century. The short film Piddington in the Mid 20th Century can be found here. You can see more photos of Oxfordshire May Garlands here.

David Cook has been researching the history of Piddington families for several years. He is presenting the information he has discovered in the form of a blog, Close to the Brook. The Diary section is a lightly fictionalised account of village life in the mid-nineteenth century, but there is much detailed factual information in the other sections.

Sources

Christine Bloxham (1998) The World of Flora Thompson, Robert Dugdale, Oxford.

David Cook (2020) Close to the Brook: An Imagined Diary of a Labouring Man Born in Piddington in 1813, Based on Real People and Real Events, closetothebrook.weebly.com/ (accessed 28 July 2020).

David Green (2000) In the Wake of Ambrosius: An Illustrated Rural History Focusing on the Upper Ray Valley, D.R. Green, Ambrosden.

Wikipedia, 'Piddington, Oxfordshire'.

A more detailed history of Piddington is available from British History Online. This consists of material taken from A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred, ed. by, Mary D. Lobel, Victoria County History, 1957.

David Cook (2020) Close to the Brook: An Imagined Diary of a Labouring Man Born in Piddington in 1813, Based on Real People and Real Events, closetothebrook.weebly.com/ (accessed 28 July 2020).

David Green (2000) In the Wake of Ambrosius: An Illustrated Rural History Focusing on the Upper Ray Valley, D.R. Green, Ambrosden.

Wikipedia, 'Piddington, Oxfordshire'.

A more detailed history of Piddington is available from British History Online. This consists of material taken from A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred, ed. by, Mary D. Lobel, Victoria County History, 1957.