History

Piddington People

John Drinkwater (1882–1937)

There are still old men in England who have never travelled beyond their own valley or woodside; to whom the landscape three miles away from their own doors is ‘foreign’ country. So it was with myself in boyhood. I knew what kind of moss grew on which walls in Piddington, and would miss a bramble creeper that the year before had been trailing on the water of a ditch. A repaired gate; a rearrangement of the glass jars of bull’s-eyes and acid drops in the tiny shop window, the cutting of a haystack, The removal of a horseshoe from the forge wall, the change of cattle from one pasture to another – these things were inevitably noted.

(John Drinkwater, An Autobiography, 1931-32)

Biography

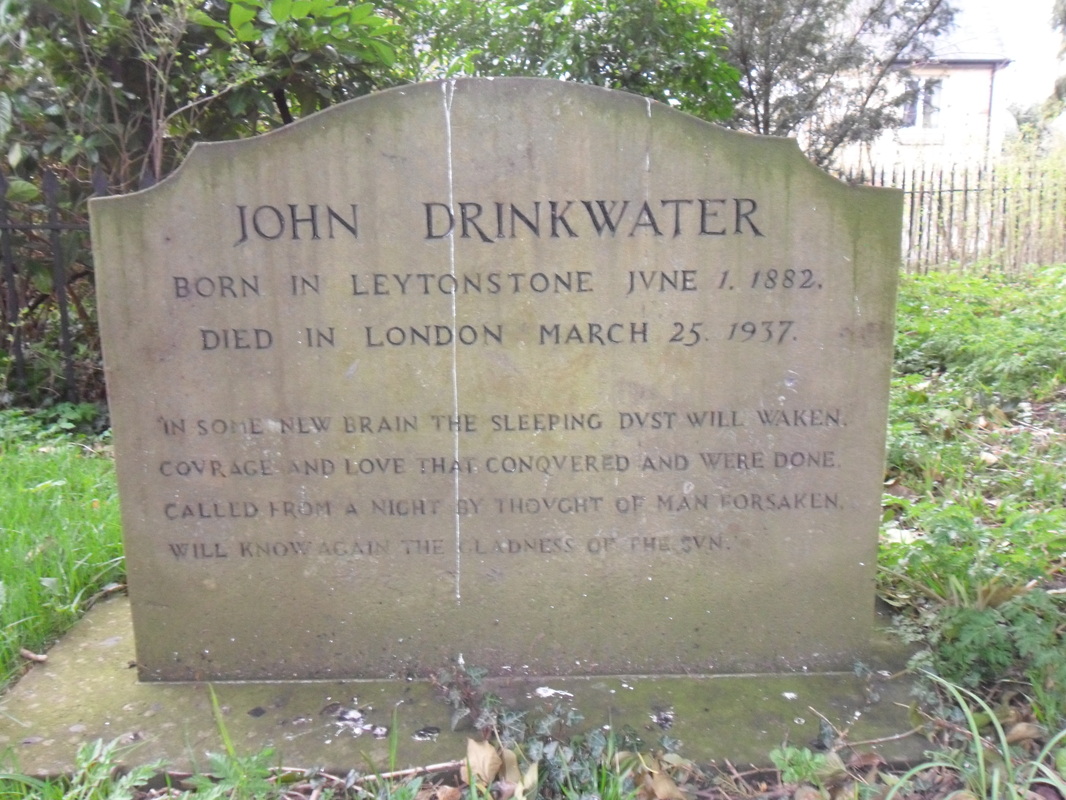

Under a tree in the churchyard of St Nicholas’ Church, Piddington, opposite the church porch, is the grave of John Drinkwater, playwright, poet and actor.

John Drinkwater was born at Leytonstone, Essex, 1 June 1882, the only son of Albert Edwin Drinkwater, a schoolmaster who came from Oxford and who later turned actor, theatrical manager and playwright, and his first wife, Annie Beck, née Brown. His father was a master at a good school in Leytonstone, who gave up teaching to go on the stage. He took his young son with him in his early days, and he met many famous actors.

When he was about nine years old, Drinkwater was sent to Oxford High School, where he spent his term time living with his paternal grandfather, John Beck Brown, an ironmonger who traded out of Cornhill, Oxford. The grandfather’s family, mainly based in Oxfordshire, were, before the advent of the railway, providing public transport by way of stage coaches from London to Oxford, and from Oxford to Banbury and Warwick.

During the school holidays, Drinkwater stayed with his great uncle, a member of the Brown family, who farmed at Piddington, where he learned to love rural life and all it meant. His love of the area remained with him all his life, and some of his best work was inspired by Piddington and the surrounding countryside. Interestingly, Drinkwater was related to Flora Thompson, author of Lark Rise to Candleford, who also had Piddington connections: Drinkwater's great-great-grandfather Thomas Beck (1756-1838) and Flora's great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Shaw née Beck (1762-1791) were siblings.

Drinkwater's father, like many actors, was determined to discourage stage ambitions in his son, and on leaving the school at the age of fifteen the boy was put into the service of the Northern Assurance Company at Nottingham, and when the firm moved to Birmingham, he went with them. However, he was soon bored and, like his father, took to the theatre, going by the name of John Darnley. With a friend, Barry Jackson, he opened the Birmingham Repertory Company and became its first manager. In addition he not only acted in its productions but was also involved in producing, directing, writing scripts and song lyrics. He retained his love of, and involvement with, the theatre all his life.

Drinkwater had always read widely, and had begun to write poetry while working as an insurance clerk. He published his first book of poems in 1903, at his own expense. His second book, Lyrical and Other Poems, was published by Samurai Press, a small, idealistic poetry publishing house, in 1908, with a further volume, Poems of Men and Hours, appearing in 1911. In the same year he became president of the Birmingham Dramatic and Literary Club, and met many artists and writers as a result.

In the period immediately before the First World War, Drinkwater was one of the group of six poets associated with the Gloucestershire village of Dymock. The other 'Dymock poets' were: Lascelles Abercrombie, Rupert Brooke, Robert Frost, Wilfred Gibson and Edward Thomas. He became close friends with Brooke, both of them contributing regularly to the influential anthology Georgian Poetry.

In 1918 Drinkwater had his first major success with his play Abraham Lincoln, which is still regularly performed in repertory theatres in the United States. In 1933 he published a collection of poems called Summer Harvest, which made reference to the Great War and his time in the Piddington countryside.

Drinkwater had married Kathleen Walpole in 1906, an actress he met through Barry Jackson's private amateur dramatic club, later to become the Pilgrim Players. They moved to London, and Drinkwater’s work brought him a degree of success both in the UK and the USA, where he toured frequently. It may have been on one of these tours that his wife fell for the brilliant Ukrainian pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch. Benno's wife, Daisy, an Australian violinist, subsequently began an affair with Drinkwater and they married in 1924. Both of them had children from their previous marriages, and he wrote children’s stories for them which he later published.

Drinkwater spent his later years living in the Cotswolds, but died in 1937, in Kilburn, London.

At his request he was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas’ Church, Piddington. His gravestone is engraved on both sides with lines from his poems.

A tower block on a 1960s council estate in Leytonstone is named after Drinkwater, as is a small development of modern houses in Piddington.

John Drinkwater was born at Leytonstone, Essex, 1 June 1882, the only son of Albert Edwin Drinkwater, a schoolmaster who came from Oxford and who later turned actor, theatrical manager and playwright, and his first wife, Annie Beck, née Brown. His father was a master at a good school in Leytonstone, who gave up teaching to go on the stage. He took his young son with him in his early days, and he met many famous actors.

When he was about nine years old, Drinkwater was sent to Oxford High School, where he spent his term time living with his paternal grandfather, John Beck Brown, an ironmonger who traded out of Cornhill, Oxford. The grandfather’s family, mainly based in Oxfordshire, were, before the advent of the railway, providing public transport by way of stage coaches from London to Oxford, and from Oxford to Banbury and Warwick.

During the school holidays, Drinkwater stayed with his great uncle, a member of the Brown family, who farmed at Piddington, where he learned to love rural life and all it meant. His love of the area remained with him all his life, and some of his best work was inspired by Piddington and the surrounding countryside. Interestingly, Drinkwater was related to Flora Thompson, author of Lark Rise to Candleford, who also had Piddington connections: Drinkwater's great-great-grandfather Thomas Beck (1756-1838) and Flora's great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Shaw née Beck (1762-1791) were siblings.

Drinkwater's father, like many actors, was determined to discourage stage ambitions in his son, and on leaving the school at the age of fifteen the boy was put into the service of the Northern Assurance Company at Nottingham, and when the firm moved to Birmingham, he went with them. However, he was soon bored and, like his father, took to the theatre, going by the name of John Darnley. With a friend, Barry Jackson, he opened the Birmingham Repertory Company and became its first manager. In addition he not only acted in its productions but was also involved in producing, directing, writing scripts and song lyrics. He retained his love of, and involvement with, the theatre all his life.

Drinkwater had always read widely, and had begun to write poetry while working as an insurance clerk. He published his first book of poems in 1903, at his own expense. His second book, Lyrical and Other Poems, was published by Samurai Press, a small, idealistic poetry publishing house, in 1908, with a further volume, Poems of Men and Hours, appearing in 1911. In the same year he became president of the Birmingham Dramatic and Literary Club, and met many artists and writers as a result.

In the period immediately before the First World War, Drinkwater was one of the group of six poets associated with the Gloucestershire village of Dymock. The other 'Dymock poets' were: Lascelles Abercrombie, Rupert Brooke, Robert Frost, Wilfred Gibson and Edward Thomas. He became close friends with Brooke, both of them contributing regularly to the influential anthology Georgian Poetry.

In 1918 Drinkwater had his first major success with his play Abraham Lincoln, which is still regularly performed in repertory theatres in the United States. In 1933 he published a collection of poems called Summer Harvest, which made reference to the Great War and his time in the Piddington countryside.

Drinkwater had married Kathleen Walpole in 1906, an actress he met through Barry Jackson's private amateur dramatic club, later to become the Pilgrim Players. They moved to London, and Drinkwater’s work brought him a degree of success both in the UK and the USA, where he toured frequently. It may have been on one of these tours that his wife fell for the brilliant Ukrainian pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch. Benno's wife, Daisy, an Australian violinist, subsequently began an affair with Drinkwater and they married in 1924. Both of them had children from their previous marriages, and he wrote children’s stories for them which he later published.

Drinkwater spent his later years living in the Cotswolds, but died in 1937, in Kilburn, London.

At his request he was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas’ Church, Piddington. His gravestone is engraved on both sides with lines from his poems.

A tower block on a 1960s council estate in Leytonstone is named after Drinkwater, as is a small development of modern houses in Piddington.

Grave in churchyard of St Nicholas' Church, Piddington

The inscription reads:

|

Front

In some new brain the sleeping dust will waken, Courage and love that conquered and were done. Called from a night by thought of man forsaken, Will know again the gladness of the sun. |

Back

Green acres, green come rain or shine What tales you are, what tales we tell, Sweet English merchandise of mine That everywhere I keep: Dear stubborn land my fathers knew, The learning of your days is well And I'll be scot and lot with you When last I go to sleep. |

Poems

Drinkwater made recordings in the Columbia Records 'International Educational Society' Lecture series. They include Lecture 10 - a lecture on 'The Speaking of Verse' (Four 78rpm sides, Cat no. D 40018-40019), and Lecture 70 'John Drinkwater reading his own poems'. You can hear them by following these links:

Listen to Lecture 10 - a lecture on 'The Speaking of Verse'

Listen to Lecture 70 - 'John Drinkwater reading his own poems'

Below are a couple of poems in which Drinkwater mentions Piddington specifically.

Listen to Lecture 10 - a lecture on 'The Speaking of Verse'

Listen to Lecture 70 - 'John Drinkwater reading his own poems'

Below are a couple of poems in which Drinkwater mentions Piddington specifically.

The Patriot

Scarce is my life more dear to me,

Brief tutor of oblivion, Than fields below the rookery That comfortably looks upon The little street of Piddington. I never think of Avon's meadows, Ryton woods or Rydal mere, Or moon-tide moulding Cotswold shadows, But I know that half the fear – Of death's indifference is here. I love my land. No heart can know The patriot's mystery, until It aches as mine for woods ablow In Gloucestershire with daffodil, Or Bicester brakes that violets fill. No man can tell what passion surges For the house of his nativity Ill the patriot's blood, until he purges His grosser mood of jealousy. And comes to meditate with me |

Of gifts of earth that stamp his brain

As mine the pools of Ludlow mill, The hazels fencing Trilly's Lane, And Forty Acres under Brill, The ferry under Elsfield hill. These are what England is to me, Not empire, nor the name of her Ranging from pole to tropic sea. These are the soil in which I bear All that I have of character. That men my fellows near and far May live in like communion, Is all I pray; all pastures are The best beloved beneath the sun I have my own; I envy none. (from Loyalties, 1919) |

A New Ballad of Charity

God knows how time shall use me yet.

For I with brain too wise have known A world corrupt, nor can forget Some evil there as still my own – Poor griefs henceforth may be alone My calendars to reckon by, But in my empires overthrown I'll keep a heart of charity. Wronged, and wrong doing, still I'll pray For gentleness to all my kind, So soon to-morrow strikes to-day. And then a day when all is blind. And the vainglory of the mind Passes, and all together lie Where nothing is but hope to find The excellence of charity. There is no virtue in us all But keeps with sin for housefellow, And, when the blade of death shall fall, Starveling and naked must we go; And none of all shall warrant show To save him from damnation by, But only this – ‘Dear God, you owe All that I dealt of charity.’ And, O you English, let us make Our hearts a little wise to-day. And learn for best religion's sake To walk awhile the homeward way. Too long we cast an alien clay And towards a far and fading sky Too long a pilgrimage we pay – For there is not our charity. |

Since I am English bred, I'll keep

A year and year my journey still By little Langdale tarns asleep, Or, with my rhymes on Bredon Hill, I will go shepherding until The shires from Severn down to Wye Are figured messages to fill My quietness with charity. And where the yellow-hammer sings From bramble blooms in Water Lane I'll make a world of sweeter things Than are in blind ambition's brain, And there I will forget the pain Of envy and the fears defy That in love's bitterness complain, – Because I walk with charity. The primroses of Bagley Wood, Old apple trees at Piddington, Helvellyn in his cloudy hood – Shall I not write them one by one, The true, the best, occasion Of all my faith before I die? For other gospellers are none To teach me holy charity. (from Seeds of Time, 1922) |

Concert inspired by John Drinkwater - photos

Here are a couple of photographs from the Concert inspired by John Drinkwater, given by Susie Self (Drinkwater's granddaughter), Michael Christie and Nigel Foster, in St Nicholas' church, 12 April 2014.

It was a wonderful evening, and all the proceeds went towards the ongoing maintenance and repair work on our beautiful church.

Download the concert programme here.

It was a wonderful evening, and all the proceeds went towards the ongoing maintenance and repair work on our beautiful church.

Download the concert programme here.